Is Two Ambiguous Figure Is a Visual Art During War 2

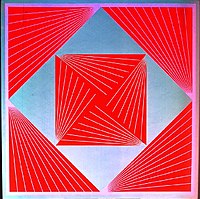

Op art, brusque for optical art, is a style of visual art that uses optical illusions.[1]

Op art works are abstract, with many improve known pieces created in black and white. Typically, they give the viewer the impression of movement, hidden images, flashing and vibrating patterns, or of swelling or warping.

History [edit]

Francis Picabia, c. 1921–22, Optophone I, encre, aquarelle et mine de plomb sur papier, 72 × threescore cm. Reproduced in Galeries Dalmau, Picabia, exhibition catalogue, Barcelona, November eighteen – December viii, 1922.

The antecedents of op fine art, in terms of graphic and color effects, tin can be traced dorsum to Neo-impressionism, Cubism, Futurism, Constructivism and Dada.[two] László Moholy-Nagy produced photographic op fine art and taught the subject in the Bauhaus. 1 of his lessons consisted of making his students produce holes in cards and so photographing them.[ commendation needed ]

Fourth dimension magazine coined the term op art in 1964, in response to Julian Stanczak's show Optical Paintings at the Martha Jackson Gallery, to mean a class of abstract art (specifically non-objective art) that uses optical illusions.[three] [4] Works at present described as "op art" had been produced for several years before Time's 1964 article. For instance, Victor Vasarely's painting Zebras (1938) is made up entirely of curvilinear black and white stripes not independent by contour lines. Consequently, the stripes appear to both meld into and burst along from the surrounding background. Also, the early black and white "dazzle" panels that John McHale installed at the This Is Tomorrow exhibit in 1956 and his Pandora series at the Constitute of Contemporary Arts in 1962 demonstrate proto-op art tendencies. Martin Gardner featured op Fine art and its relation to mathematics in his July 1965 Mathematical Games column in Scientific American. In Italian republic, Franco Grignani, who originally trained as an architect, became a leading forcefulness of graphic design where op art or kinetic art was central. His Woolmark logo (launched in Great britain in 1964) is probably the most famous of all his designs.[v]

Op art perhaps more than closely derives from the constructivist practices of the Bauhaus.[6] This German language school, founded by Walter Gropius, stressed the relationship of form and part within a framework of analysis and rationality. Students learned to focus on the overall blueprint or entire composition to present unified works. Op art too stems from trompe-fifty'œil and anamorphosis. Links with psychological enquiry take likewise been made, particularly with Gestalt theory and psychophysiology.[2] When the Bauhaus was forced to shut in 1933, many of its instructors fled to the The states. There, the movement took root in Chicago and somewhen at the Blackness Mountain College in Asheville, North Carolina, where Anni and Josef Albers eventually taught.[7]

Op artists thus managed to exploit diverse phenomena," writes Popper, "the later on-image and consecutive move; line interference; the effect of dazzle; ambiguous figures and reversible perspective; successive colour contrasts and chromatic vibration; and in three-dimensional works different viewpoints and the superimposition of elements in infinite.[2]

In 1955, for the exhibition Mouvements at the Denise René gallery in Paris, Victor Vasarely and Pontus Hulten promoted in their "Yellow manifesto" some new kinetic expressions based on optical and luminous phenomenon as well as painting illusionism. The expression kinetic art in this modern grade first appeared at the Museum für Gestaltung of Zürich in 1960, and found its major developments in the 1960s. In most European countries, it generally includes the form of optical fine art that mainly makes use of optical illusions, like op art, every bit well as fine art based on movement represented by Yacov Agam, Carlos Cruz-Diez, Jesús Rafael Soto, Gregorio Vardanega or Nicolas Schöffer. From 1961 to 1968, the Groupe de Recherche d'Art Visuel (GRAV) founded by François Morellet, Julio Le Parc, Francisco Sobrino, Horacio Garcia Rossi, Yvaral, Joël Stein and Vera Molnár was a collective grouping of opto-kinetic artists that—according to its 1963 manifesto—appealed to the directly participation of the public with an influence on its behavior, notably through the use of interactive labyrinths.

Some members of the group Nouvelle tendance (1961–1965) in Europe also were engaged in op art every bit Almir Mavignier and Gerhard von Graevenitz, mainly with their serigraphics. They studied optical illusions. The term op irritated many of the artists labeled nether information technology, specifically including Albers and Stanczak. They had discussed upon the birth of the term a amend label, namely perceptual art.[eight] From 1964, Arnold Schmidt (Arnold Alfred Schmidt) had several solo exhibitions of his large, black and white shaped optical paintings exhibited at the Terrain Gallery in New York.[9]

The Responsive Center [edit]

In 1965, between February 23 and April 25, an exhibition chosen The Responsive Center, created by William C. Seitz, was held at the Museum of Modern Fine art in New York Metropolis and toured to St. Louis, Seattle, Pasadena, and Baltimore.[10] [11] The works shown were wide-ranging, encompassing the minimalism of Frank Stella and Ellsworth Kelly, the smooth plasticity of Alexander Liberman, the collaborative efforts of the Anonima group, alongside the well-known Victor Vasarely, Richard Anuszkiewicz, Wen-Ying Tsai, Bridget Riley and Getulio Alviani. The exhibition focused on the perceptual aspects of art, which result both from the illusion of motility and the interaction of color relationships.

The exhibition was a success with the public (visitor attendance was over 180,000),[12] but less and then with the critics.[thirteen] Critics dismissed op art as portraying nothing more trompe-l'œil, or tricks that fool the eye. Regardless, the public's acceptance increased, and op art images were used in a number of commercial contexts. I of Brian de Palma'due south early on works was a documentary film on the exhibition.[14]

Method of operation [edit]

Black-and-white and the figure-basis relationship [edit]

Op art is a perceptual experience related to how vision functions. It is a dynamic visual art that stems from a discordant figure-ground relationship that puts the two planes—foreground and background—in a tense and contradictory juxtaposition. Artists create op art in two main ways. The first, best known method, is to create effects through pattern and line. Oft these paintings are black and white, or shades of gray (grisaille)—as in Bridget Riley's early paintings such every bit Current (1964), on the embrace of The Responsive Eye itemize. Hither, black and white wavy lines are shut to one another on the canvass surface, creating a volatile figure-basis relationship. Getulio Alviani used aluminum surfaces, which he treated to create light patterns that change equally the watcher moves (vibrating texture surfaces). Another reaction that occurs is that the lines create afterwards-images of certain colors due to how the retina receives and processes lite. As Goethe demonstrates in his treatise Theory of Colours, at the border where low-cal and dark meet, colour arises because lightness and darkness are the two central properties in the cosmos of color.[ citation needed ]

Colour [edit]

Starting time in 1965 Bridget Riley began to produce color-based op fine art;[xv] however, other artists, such equally Julian Stanczak and Richard Anuszkiewicz, were always interested in making color the main focus of their work.[sixteen] Josef Albers taught these two main practitioners of the "Colour Function" school at Yale in the 1950s. Often, colorist piece of work is dominated by the same concerns of figure-footing movement, but they have the added element of contrasting colors that produce different furnishings on the eye. For case, in Anuszkiewicz's "temple" paintings, the juxtaposition of two highly contrasting colors provokes a sense of depth in illusionistic three-dimensional space then that it appears as if the architectural shape is invading the viewer'south space.

-

Intrinsic Harmony, by Richard Anuszkiewicz, 1965

Exhibitions [edit]

- L'Œil moteur: Art optique et cinétique 1960–1975, Musée d'fine art moderne et contemporain, Strasbourg, French republic, May thirteen–September 25, 2005.

- Op Art, Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, Federal republic of germany, Feb 17–May 20, 2007.

- The Optical Border, The Pratt Institute of Fine art, New York, March 8–April 14, 2007.

- Optic Nerve: Perceptual Art of the 1960s, Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus, Ohio, February sixteen–June 17, 2007.

- CLE OP: Cleveland Op Art Pioneers, Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio, April nine, 2011–Feb 26, 2012

- Bridget Riley has had several international exhibitions (e.g. Dia Centre, New York, 2000; Tate Britain, London, 2003; Museum of Gimmicky Art, Sydney, 2004).

See also [edit]

- List of Op artists

- Divisionism

- Kinetic art

- Binakael (similar patterns in traditional Filipino textiles)

- Chubb illusion

- Cornsweet illusion

- Impossible object

- Lilac attorney

- M. C. Escher

- Mach bands

- Multistable perception

- Optical illusion

- Pattern glare

- Perception

- Same colour illusion

- Trompe-fifty'œil

- Zippo (fine art)

References [edit]

- ^ Artspeak, Robert Atkins, ISBN 978-1-55859-127-ane

- ^ a b c "The Collection - MoMA". The Museum of Modern Fine art. Retrieved Nov 5, 2017.

- ^ Jon Borgzinner. "Op Art", Fourth dimension, October 23, 1964.

- ^ "Op-Art: History, Characteristics". www.Visual-Arts-Cork.com. Retrieved November 5, 2017.

- ^ "The Hypnotic, Listen-angle Work of Italian Designer Franco Grignani". Eye on Design. 2019-06-28. Retrieved 2019-12-15 .

- ^ "Op-Art: History, Characteristics". world wide web.visual-arts-cork.com . Retrieved 2019-12-xv .

- ^ "Black Mountain College Motility Overview". The Art Story . Retrieved 2019-12-15 .

- ^ Bertholf. "Julian Stanczak: Decades of Light" Yale Press

- ^ "A Brief History of the Terrain Gallery". TerrainGallery.org. Archived from the original on April 3, 2010. Retrieved November 5, 2017.

- ^ Seitz, William C. (1965). The Responsive Center (exhibition catalog) (PDF). New York: Museum of Mod Fine art. OCLC 644787547. Retrieved January 23, 2016.

- ^ "The Responsive Eye" (PDF) (Press release). New York: Museum of Modern Fine art. Feb 25, 1965. Retrieved Jan 23, 2016.

- ^ Gordon Hyatt (writer and producer), Mike Wallace (presenter) (1965). The Responsive Center (Television production). Columbia Dissemination System, Inc. Archived from the original on 2013-01-03. (Available on YouTube in three sections.)

- ^ "MoMA 1965: The Responsive Eye". CoolHunting.com. Archived from the original on September 28, 2009. Retrieved November five, 2017.

- ^ Brian De Palma (managing director) (1966). The Responsive Eye (Motion picture show).

- ^ Hopkins, David (September 14, 2000). After Modernistic Art 1945-2000. OUP Oxford. p. 147. ISBN9780192842343 . Retrieved Nov 5, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ See Color Function Painting: The Art of Josef Albers, Julian Stanczak, and Richard Anuszkiewicz, Wake Forest University, reprinted 2002

Bibliography [edit]

- Frank Popper, Origins and Development of Kinetic Art, New York Graphic Society/Studio Vista, 1968

- Frank Popper, From Technological to Virtual Fine art, Leonardo Books, MIT Press, 2007

- Seitz, William C. (1965). The Responsive Eye (PDF). New York: Museum of Modern Fine art. Exhibition catalog.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link)

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Op art. |

| | Look upwards op art in Wiktionary, the free lexicon. |

- Op Art - Tate Gallery Glossary Terms

- Opartica - Online Op Art Making Tool

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Op_art

0 Response to "Is Two Ambiguous Figure Is a Visual Art During War 2"

Post a Comment